Índice

Amateur Immigrant.

This project was realized between 2019 and 2022 with the support of a National System of Creators grant from the Mexican National Fund for Arts and Culture (FONCA). Amateur Immigrant proposes a reflection on immigration taking as a point of departure both my own experience of political exile, as well as the experience of my great granduncle, a Uruguayan who went to Spain to fight in the International Brigades supporting the Republican cause.

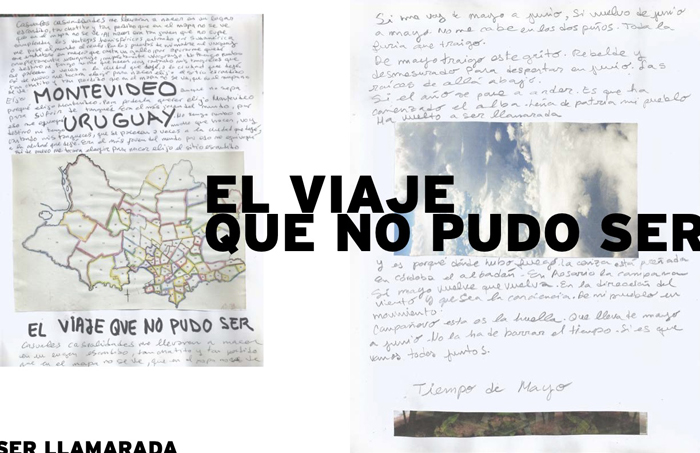

The film seeks to examine a personal psychogeography traced between Mexico City and Montevideo, as well as the trajectories of my great granduncle weaving between Uruguay, Spain, France and Austria.

Amateur Immigrant consists of three components:

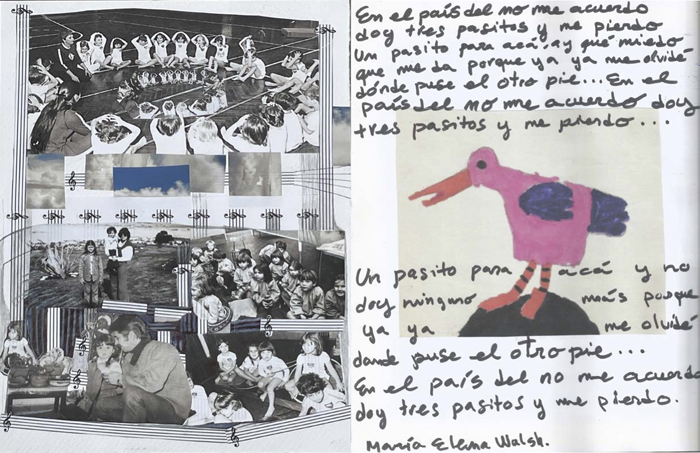

-A series of sonic actions called Emotional Scores.

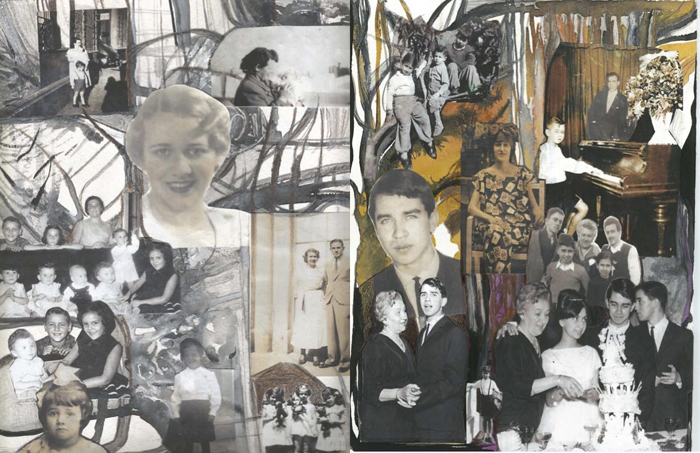

-The film itself (with a duration of 1:30:24) whose characteristics share something with the essay film, and which contains, in an abbreviated form, the sonic actions, trajectories, archival material, and testimonies that, as voices, are the protagonists that configure the narrative.

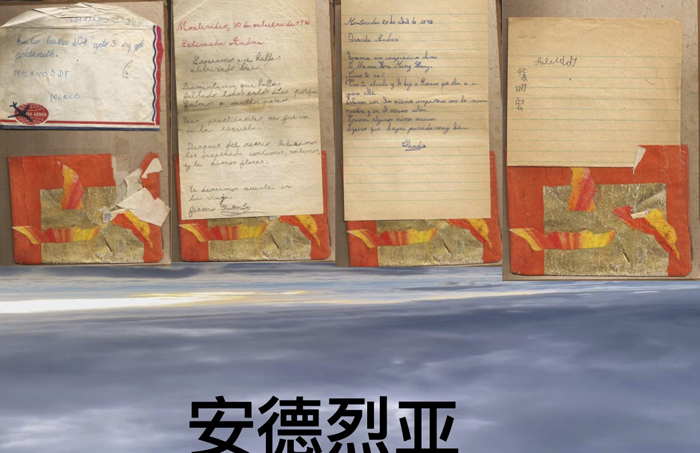

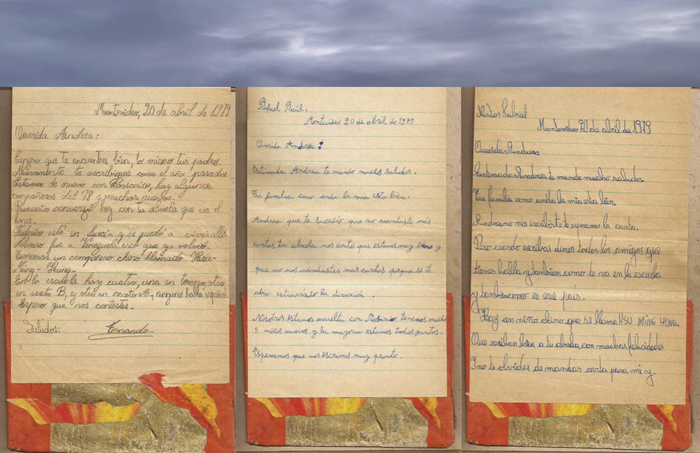

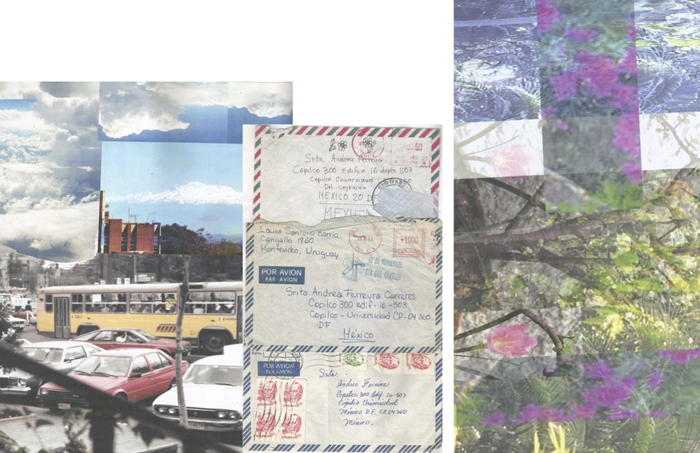

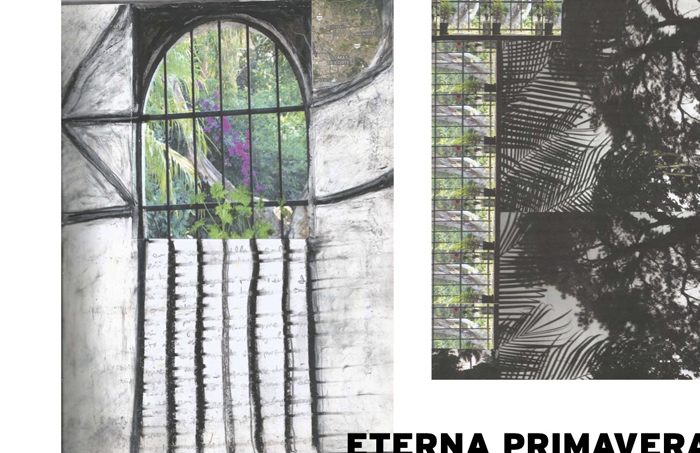

-A logbook containing texts, collages, watercolors and photos, which serves as a record of the entire process and investigation.

The full-length film required a period of four years to complete, one year longer than the grant period, finally premiering in 2024.

Project background:

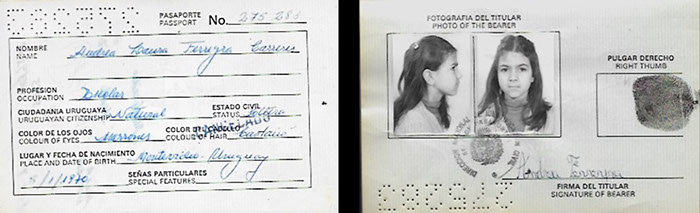

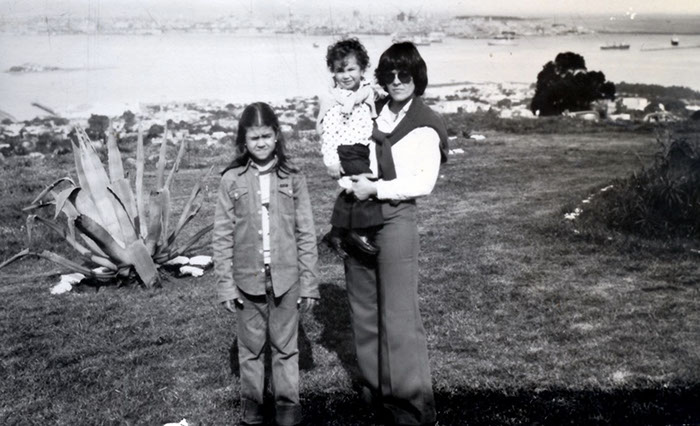

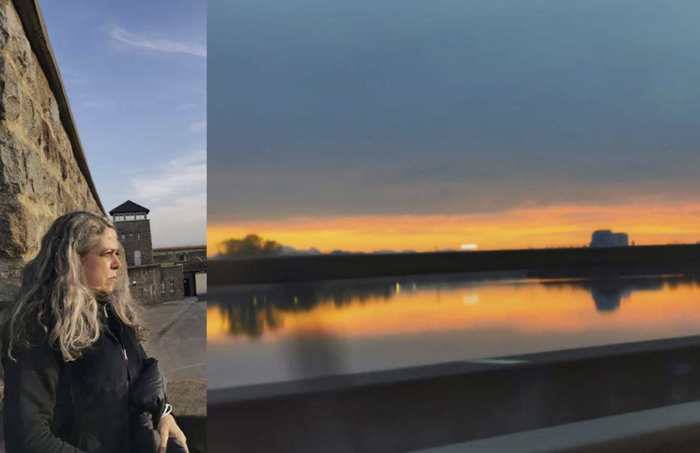

I lived through a political exile that brought me to Mexico in 1978, at the age of eight. I had never addressed this subject in my artistic practice—my practice generally not being articulated around autobiographical coordinates, or at least not explicitly. I wanted to delve deeper into this theme via my parents’ testimonies. By sharing their experience, as microhistory, they also project the experience of their generation. I became aware that they’re getting older and that this was the opportunity to rescue their story, which is also the story of many others.

At the same time, an astonishing story emerged that spurred me on and contributed to the development of these ideas and their processes.

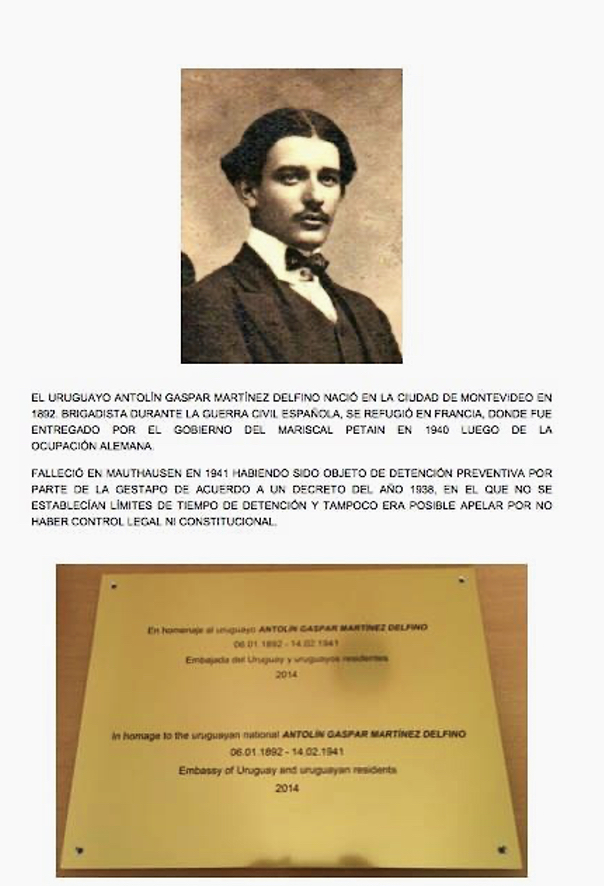

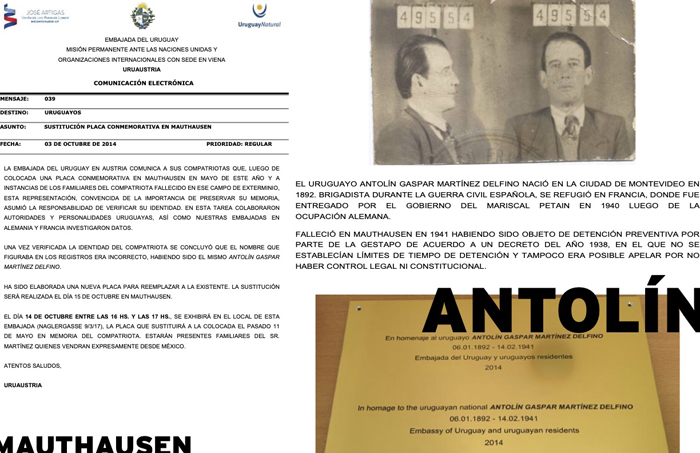

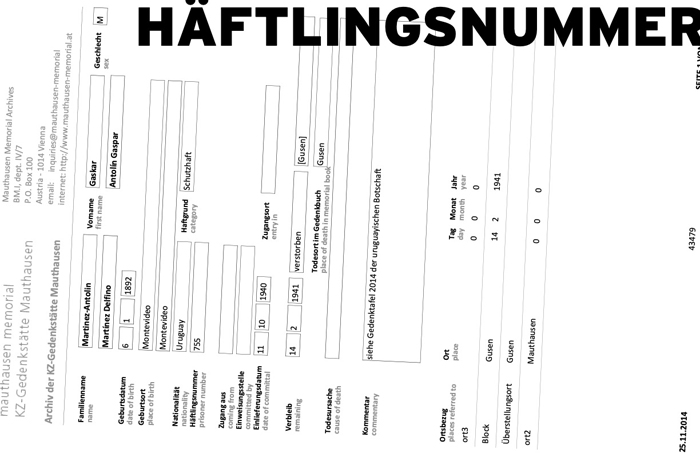

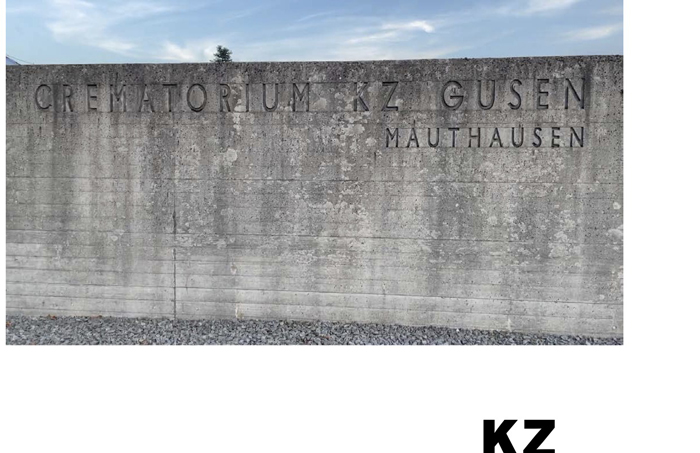

At some point in 2014 my mother, by pure coincidence, came across an article published in a Uruguayan newspaper which mentioned the one and only Uruguayan national who had died in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Reading the name and date of birth of this man she realized, or intuited, that the person in question was her great uncle—even though his name didn’t match entirely with the one printed: Gaskar Martínez Antolín, born January 6, 1892.

Faced with this discovery, my mother asked her brother in Uruguay to search for the birth certificate. She then wrote an email, including the birth certificate, to the then Uruguayan ambassador in Austria, Bruno Faraone. Faraone replied that they would look into the matter.

Sometime later my mother received another email which informed her that, after checking the information with the Uruguayan embassies in France and Germany, they had confirmed that the man in question was indeed her great uncle, Antolin Gaspar Martinez Delfino.

On May 8th of that year, as part of a procession that honors the victims of the Mauthausen camp, the embassy had unveiled a new plaque in the Memorial with the name that their preliminary investigation had yielded.

In the email confirming the identity of my mother's great-uncle, the ambassador invited her to witness, though no longer as an official ceremony, the replacement of the plaque with one bearing the correct name.

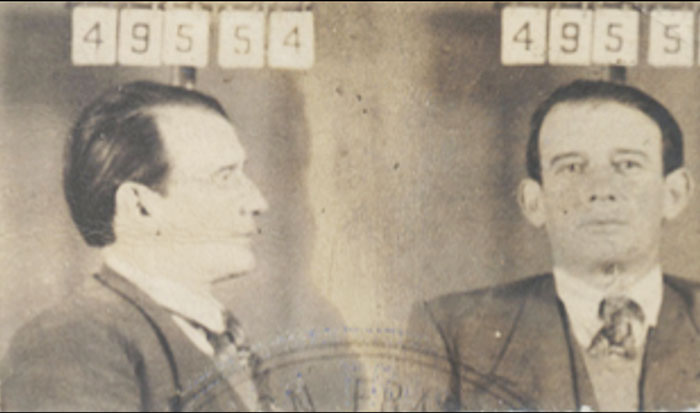

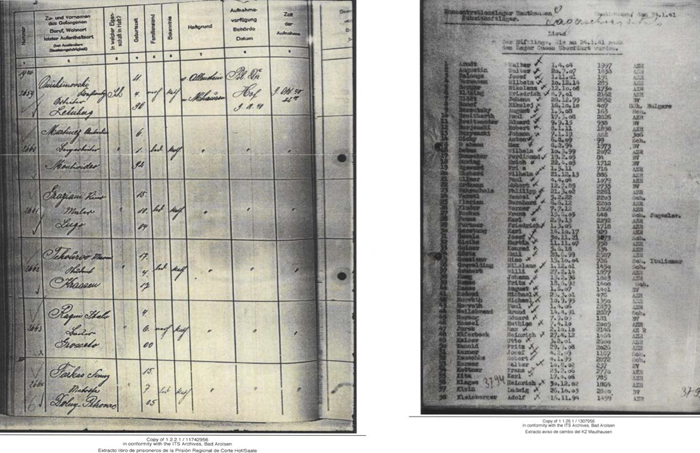

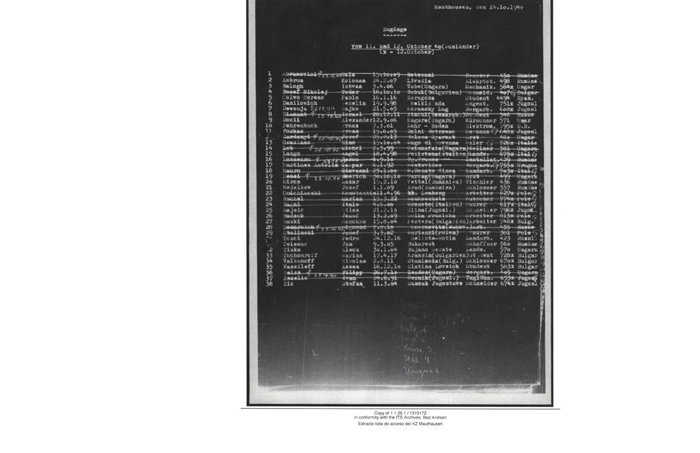

So it was that we traveled to Vienna in October 2014, staying at the ambassador's residence to attend the replacement of the plaque. My mother opened an investigation with the International Tracing Service, which subsequently uncovered the route that Antolin took via Barcelona to cross to France in 1939, his subsequent arrest in Gurs, followed by his release, his journey to Pas de Calais where he went to work in a mine, and his arrest by the Gestapo in October 1940, upon which he was trasported first to Germany, then to Mauthausen, and from there, already very ill, to Gusen, where he died in February 1941.

This whole experience was very moving. I decided to approach it in conjunction with my interest in reflecting on the immigrant condition, where the process of adaptation to a new environment requires one to position themself as an observer, someone separate from the reality that, at the same time, they are immersed in.

Additionally, there was the ideological connection, although with certain nuances: my parents were exiled because they belonged to the Communist Party, and, during the military dictatorship in Uruguay, there were already many comrades who had been imprisoned, disappeared, or were in hiding; they might have been next, and so they had to leave.

Antolin, according to the investigation, was not a communist or socialist, he was an anti-fascist born in Uruguay to a Spanish father who volunteered in the International Brigades. Many foreigners like him went to Spain to fight for the Second Republic, be it out of this affiliation or others—what was clear was the advance of fascism in Europe, and the fight against it brought together various political currents and ideological positions. What is also clear is that Antolin, along with many others, knew that he was probably walking to his death.

Índice

Emotional Scores. Sonic Actions.

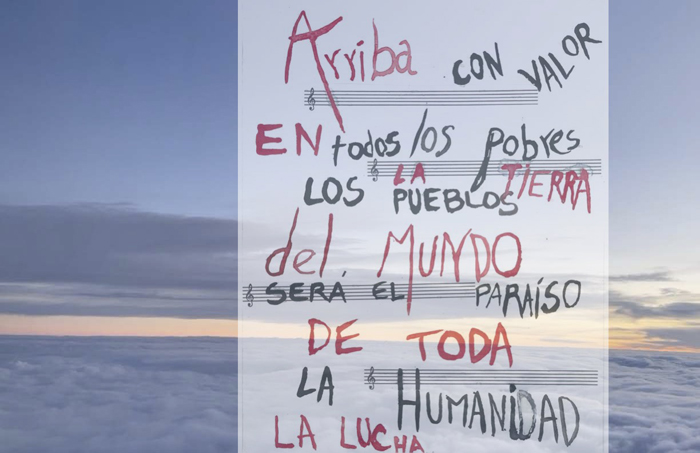

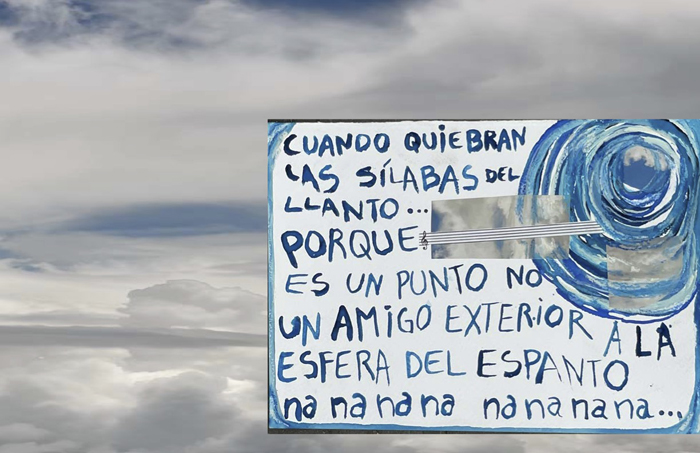

Throughout the entire process of the project, music began, more and more, to occupy a leading role. I developed what I call Emotional Scores: the music that floods my memory—particularly that which triggers memories of my early childhood in Uruguay and the first years of exile in Mexico.

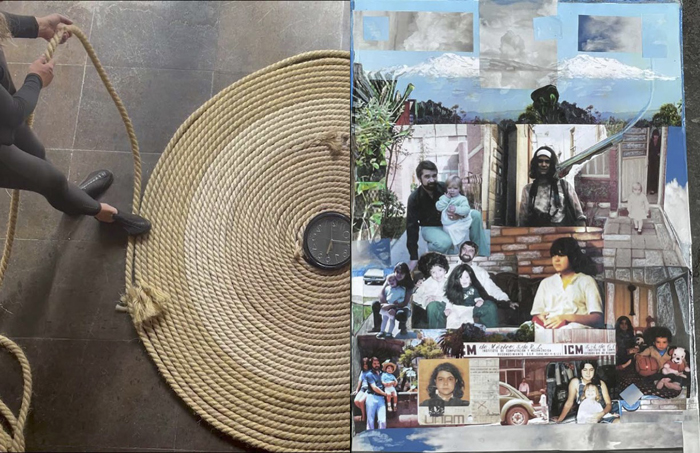

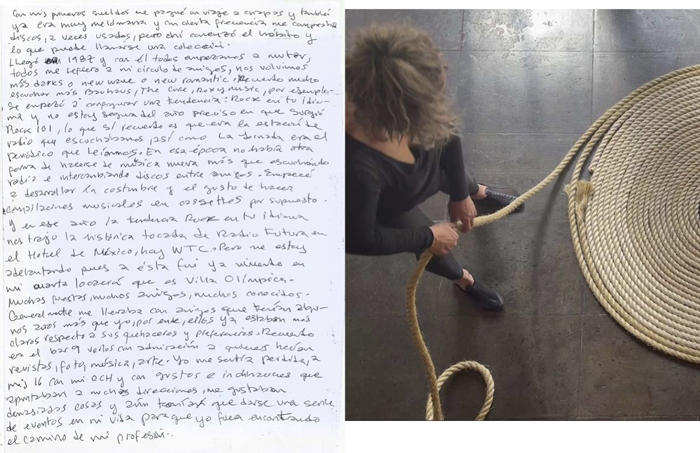

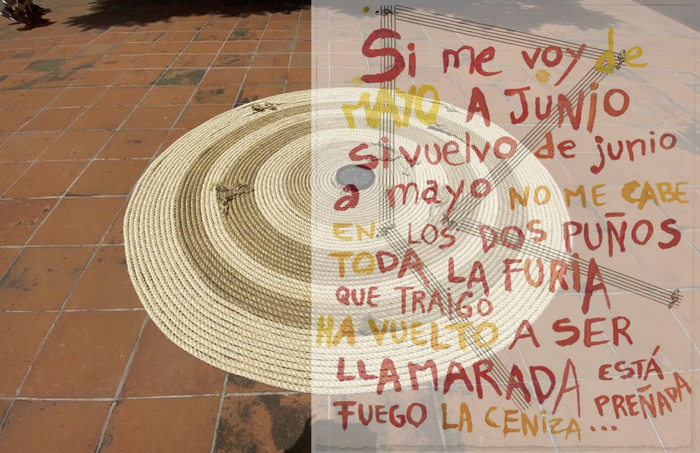

Emotional Score No. 0. Whirlwind Clock.

I realized an action that gave origin to the subsequent ones, but at the same time encompasses them.

This action is related to my 1993-piece Torbellino, a piece that I took up again in 2019 in the context of an exhibition where it was presented. I didn’t want to repeat the original action, but having the material at hand gave rise to the tracing of a winding spiral around a clock, and I incorporated the idea of the Emotional Score into the sculpture. Thus, I whistle all the songs that appear in the other Scores throughout the action of placing the rope around the clock.

Emotional Score No.1. It’s Progreso not Montevideo.

This action was originally meant to take place in Montevideo, but because of the pandemic I had to carry it out in Puerto Progreso, Yucatan.

Here I whistle three songs: A la ciudad de Montevideo, El pueblo unido jamás será vencido and the Internationale.

With a static camera whose frame served as a window, I walked back and forth, whistling.

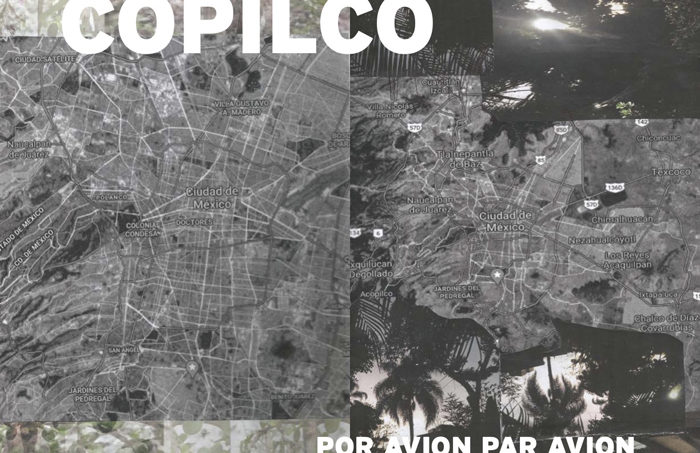

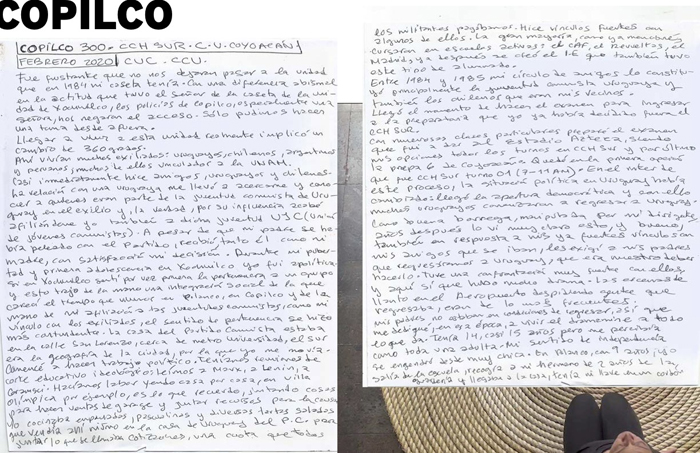

Emotional Score No.2. Mexico City.

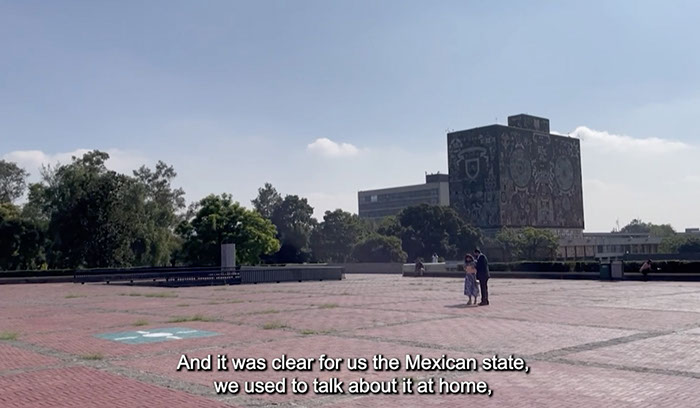

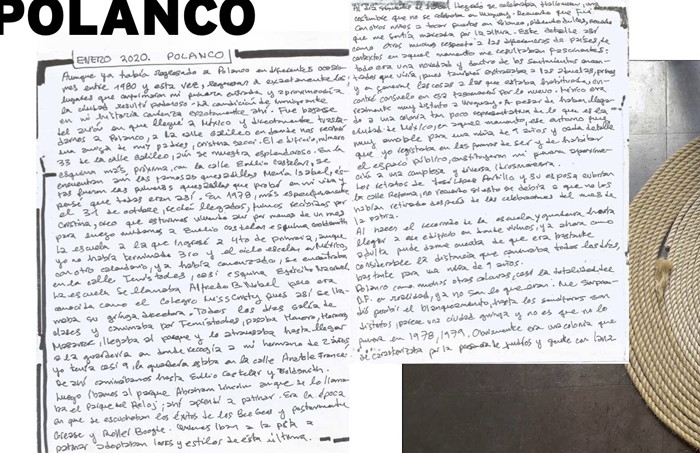

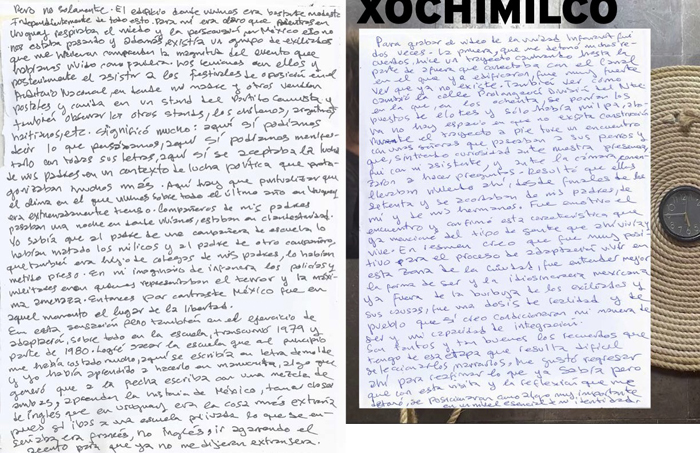

For this action I decided on a frontal framing and on the utilization of several specific sites, specifically the places where I lived between 1978 and 1995 (the year in which I was naturalized as Mexican). The use of several locations served to speak about Mexico City, since a single site couldn’t represent its diversity.

The locations were: Polanco, Xochimilco, Copilco 300, Villa Olímpica, Coyoacán and a pedestrian bridge, understanding it as a non-place—a place that could be anywhere.

The songs were Tiempo de mayo, La Cumparsita and La Bikina, the latter as a first association I had as a child with Mexico, since the Cantinflas program that was broadcasted in Uruguay in the seventies used this song in its introduction.

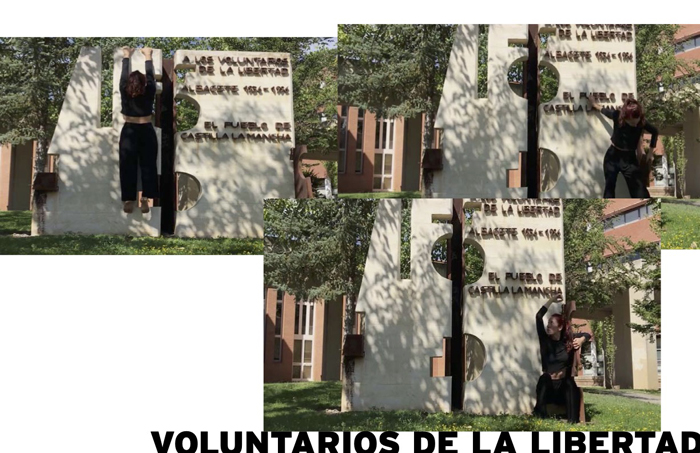

Emotional Score No.3. Albacete, Spain.

At the monument to the International Brigades in Albacete, working in a collaboration with the Valencian Cristina Gómez, I took on a few albums by a Spanish band from the seventies: Aguaviva. I shared this music with Cristina, and she improvised using the language of dance, which is her craft.

Later, to reinforce the logic of collaboration, I dubbed the audio of the video whistling first ¡Ay, Carmela! then Llanto and Un pueblo, all by Aguaviva.

Emotional Score No.4. Hénin Beaumont, France.

Hénin Lietard Cite Darcy 409 is the address that appears in the documents where Antolin was arrested by the Gestapo. This address no longer exists as such, since a couple of communes were merged when the mine, where Antolin in fact worked, was closed.

The region surrounding what used to be the mining basin, specifically Hénin Beaumont, was the place where I carried out the action.

The songs were: La Cumparsita, ¡Ay, Carmela! and Le Chant des Partisans. The relationship between these three songs tells the story of Antolin.

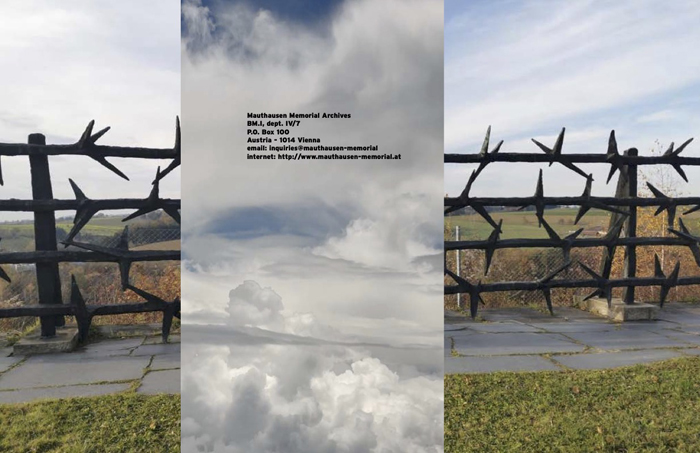

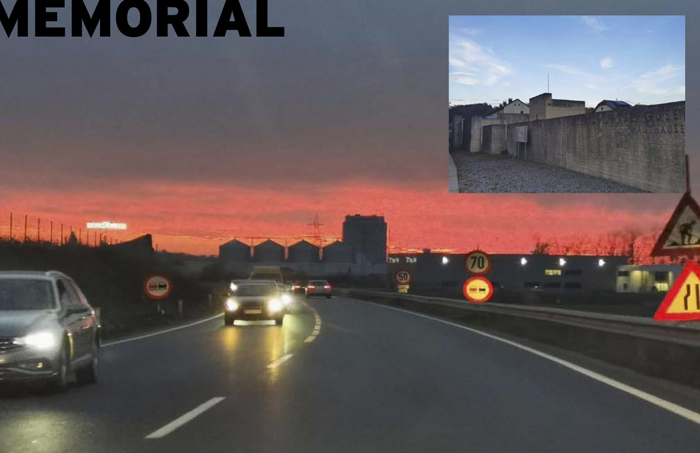

Emotional Score No.5. Mauthausen, Austria.

For this action I approached several songs from the album Canción con todos by Armando Tejada Gómez; I executed the action in two very different spaces in Mauthausen.

Emotional Score No.6. Gusen, Austria.

The idea of going to Gusen was last minute, but at the same time, it was very important. It was the place where Antolin died.

Gusen is very small in relation to Mauthausen, but just as ominous.

Here the songs were the same as Hénin Beaumont's: La Cumparsita, ¡Ay, Carmela! and Le Chant des Partisans.

I decided to turn my back to the camera and whistle facing the wall which provoked a very special acoustic phenomenon: my whistling was heard along the whole perimeter of the camp, which is surrounded by houses.

Índice

Amateur Immigrant.

Length: 1:30:24.

Synopsis:

Amateur Immigrant is an audiovisual piece by Andrea Ferreyra that reflects on her own experience of political exile and immigration, traced between Montevideo and Mexico City, as well as that of her great granduncle, whose life story unfolded between Uruguay, Spain, France and Austria.

Testimonies are interwoven in the film to contextualize the central story and provide other microhistories. Ferreyra also realized a series of sonic actions in the places that compromise the psychogeographies.

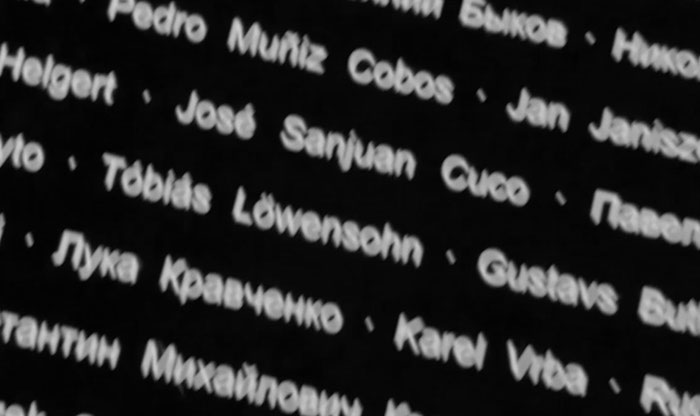

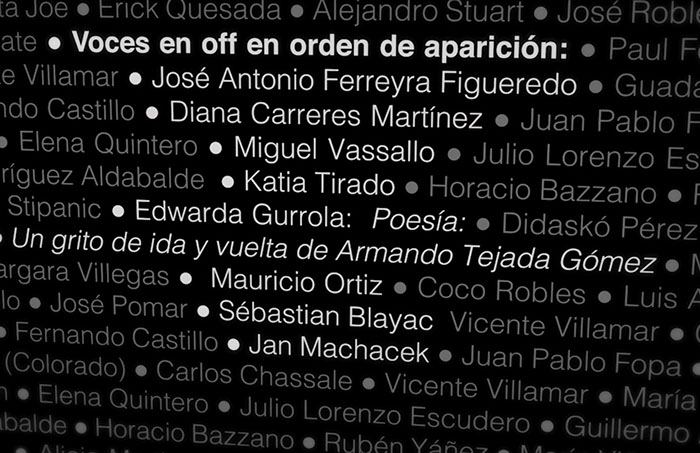

Miguel Vassallo and Katia Tirado contributed from their own experience to the analysis of the reality of Mexico. Mauricio Ortiz shared the story of his grandfather who disappeared in Valencia during the civil war. Sèbastian Blayac spoke about his grandparents who lived through the Nazi occupation in France, and Jan Machacek reflected on his Austrian condition in regard to Mauthausen and its historical period.

The voice of Edwarda Gurrola gave life to the poem Un grito de ida y vuelta, by Armando Tejada Gómez, a text that establishes a pause between the stories that are told.

Amateur Immigrant premiered on April 20, 2024, at Cine Tonalá and will travel to other cinemas in Mexico City, and other cities in Mexico and around the world.

Índice

Índice